Why – in wealthy countries where food is plentiful – do people go hungry?

In 2022 research emerged from New Zealand that examined food poverty in the country. The findings challenged a perception of those who struggle to feed their families frequently held by those who don’t: that hunger in places such as New Zealand is the result of bad individual choices. Often, blame is implicitly laid at the feet of individuals. And responses and interventions subsequently focusing on how individuals can be compelled or supported to make better choices. Similarly, research into foodbanks in the UK found that Victorian notions of deserving and undeserving poor still prevail, with the researcher observing that

Some providers framed the use of food charity as a ‘choice’ borne of poor life decisions or inadequate cooking abilities…These narratives drew legitimacy from and further legitimated the classic deserving/undeserving divide while individualising food insecurity and obscuring the systemic issues which give rise to the use of food charity…[There was an] operationalisation of the deserving/undeserving binary and ascription to stigmatising behavioural narratives of ‘choice’…people were divided, not only by bureaucratic processes, but also by the idea that some people were undeserving of food

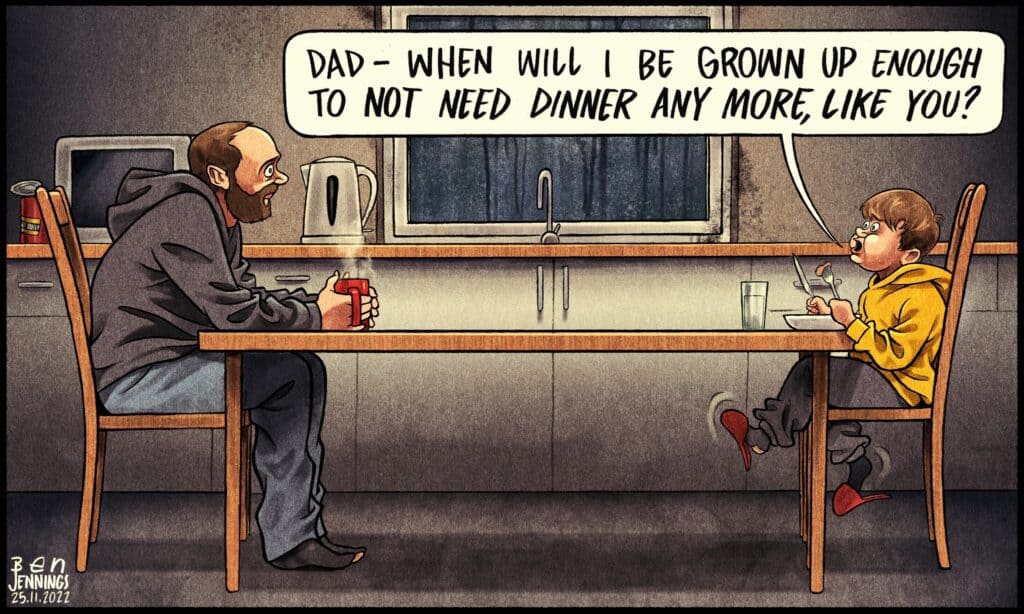

What the researchers in New Zealand found (which reinforces earlier findings in the UK) was in fact that parents tend to make choices that are not so much bad, but hard. Choices which reflect the hard contexts in which they live. For example, “parents went without food in order to feed their children.” The research found that many parents did not need more lessons about what and how to cook, as they “had good nutritional knowledge.” They reported that “mothers in particular worked very hard to protect their children from knowing the extent of the poverty and hunger within the home” (this again mirrors the experience of many in the UK).

What needs to be more talked about, better understood, and underpin action is that rather than bad choices or lack of individual knowledge, hunger in countries such as New Zealand is driven by low incomes. Incomes so low that they limit the resources people have available to buy goods (see here and here). Hunger is made worse by the rising costs of living which makes stretched family budgets stretch less far. Hunger is a result of people only being able to find work that is insecure or which doesn’t come with enough hours. Hunger is linked to unaffordable housing and not having access to land to grow one’s own food.

Taking onboard these realities demands looking upstream to how the economy operates: the terrain of jobs, what sort of work is paid for, costs of goods and services, and provision of amenities.

It demands that instead of simply expressing sympathy with individuals at the sharp end and offering them food parcels if they are deemed deserving enough or putting on cooking classes on the assumption that it is cooking skills that are lacking, that there is compassion for those experiencing hunger. Such compassion would then drive action into the realm of the economy. It would shape how we think about the economy and the expectations we have of it.

Compassion demands the very opposite of laying all the onus for change on people already navigating the consequences of decisions by others, decisions that are often taken in remote rooms where people experiencing hunger don’t have a seat at the table.

The challenge though, as the researchers in New Zealand explain (and see also), is that:

People who have resources to share are viewed as altruistic, compassionate and empathetic when they give to charity. In comparison, people in need of charity feel a sense of shame and stigma at having their lack and inadequacy exposed…people who need help to meet a basic need, such as food, feel humiliated.

In other words, those who are already succeeding out of today’s economy are rewarded with gratitude and positive reputation when they share a little, whereas those who are struggling are expected to feel grateful for the charity they are given, and often feel shame and humiliation at their struggle to navigate the structural barriers and burdens the economy and society puts in their way.

A compassionate approach would turn charity on its axis. It would be less about how individuals can be made more resilient (to withstand burdens), or empowered (to carry more burdens): it would be more about lessening those burdens in the first place by asking where they came from, who and what holds them in place, and even who benefits from their existence?

Translating those compassionate questions to the economy would mean the priority becomes ensuring the economy operates in a way that delivers for more people, rather than just a fortunate few. And that means grappling with the purpose, design, and delivery of the economy. It means supporting and implementing policy instruments that ensure, for example:

- That people are paid enough

- That profitability is a means, rather than a goal in its own right

- That economic activity is generated from the local up, rather than hoping in vain for it to trickle down

- That basic needs such as shelter and education and health are not divvied up on the basis of ability to pay, but delivered on the basis of them being rights of citizens

- That sources of unearned wealth such as inheritance and rent and land values are taxed more than incomes

- That economic activities which make money from people’s struggles or profit as a result of doing harm to the planet are, if not banned, at least marginalised

- Prices of goods and services reflect their true cost in terms of what it took to make them – both in environmental terms and the people involved being compensated for their efforts

- How success is measured is about outcomes which reflect what people and planet need

So in a world where hunger prevails, where some have hoards of wealth and others lack the basics, compassion is not just about how we treat each other on a one-to-one basis. It is not just about how we care for certain strangers or groups whose hurt we seek to understand and respond to. It is about moving away from the pervasive individualism on which our economic model hinges to an understanding of and actions based on our deep interdependence and the structural causes of hardship. Compassion is about no less than economic system change.