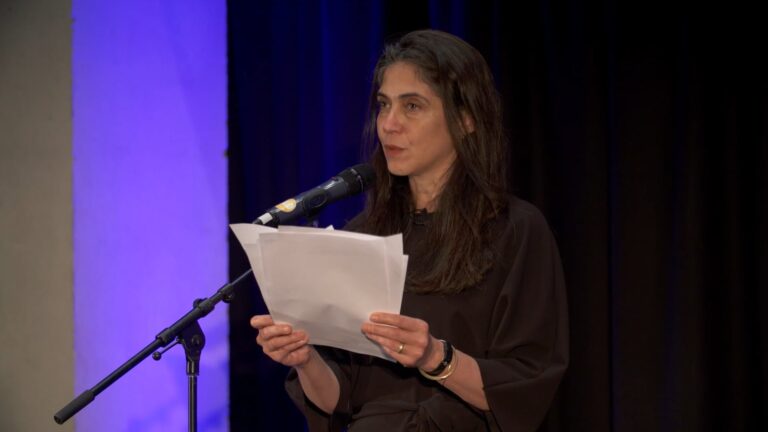

Interrogating Learning, a poem by Marjorie Lotfi, commissioned for Edinburgh Futures Conversations, The Future of Education: Crisis

i. WHAT have you learned?

When asked this question, how will

a woman answer? For a moment

she’s back in her mother’s belly, the heart

beating out a rush of cortisol or the warm

dream of sleep, listening through a barrier

of skin and blood before even her own first

breath. And then the day she’s born, blinking

at the bright of daylight, candle, bulb, hearing

the low buzz of electric and the sudden clarity

of a voice she knows already, learning it again.

There have been a thousand things to learn

in every day I’ve been alive, the woman thinks,

and I am fifty-three this year. She’s learned

how seasons circle, that winter to spring pushes

shoots in early warmth to test the weather,

to square her shoulders when speaking,

how to carry the brightest colours on the body,

and to test the temperature of bathwater

on the inside of a wrist — one drop, then two,

to speak slowly but not loudly to the dying,

how endings contain gifts (even the white

bloom of wild garlic is edible before it blows

into spring snow), how both patience and light

is needed to thread a needle, how elderflower

must be picked as the dew is lifting, that honey

soothes a raw throat but it’s ginger that settles

the stomach, how to recognise a storm approaching —

as this one — in the bones, and that mint leaves,

when planted, will take the whole of a garden plot

if not contained in a pot (a useful metaphor,

she realises, for so much else). “What have I

learned?” she says aloud. “What a strange question.”

ii. Then WHERE did you learn?

“Do you mean what did I learn in school?” she asks

and notes the nod. “Without being taught,

I learned two languages, neither of them mine,

to avoid punishment, to panic about deadlines.

School trained me in punctuality. I learned

the sound of a fire bell, the nuclear alarm, to fold

into the brace position. E = MC2, the 1410 Battle

of Grunwald, i before e except after c, and biology

so unrelated to my own body even now.

I think how useful it could have been.

I learned that grades were mostly about remembering –

dates, names of victors, the precise ordering of numbers

and symbols to tell us how the world unfolds.

I learned that while I was memorising all

the data, all the facts, I was also trying to forget.

I learned there will never be any pause as fun

as a school break, the drifting home, unhurried,

with friends. I learned how to hide my lunchbox,

and what its contents – a jam sandwich,

an orange – signalled. I learned to write

my own name, the correct sounds of words

in my mouth. I learned that God said

let there be light (but not that daylight

and darkness arrive at the same time).

In school I learned the most important

lesson: how to learn, how we study mostly

to find answers to questions we don’t realise

we carry, to see the whole library of possibilities.

iii. And WHO was your teacher?

The woman thinks not just of her mother, and her

mother’s parents and her father, and her father’s

parents teaching her about pennies and the correct

way to drink tea as a lady (kamrang), how to hold

playing cards to the chest, but of the aunt

and her perfect tadiq, how the Persian family

smuggled the rules of taarof, politeness, out

of the country, but also the librarian who looked

the other way when she read books banned

at home, and her brother, too, his failure

to remember how they got out of Tehran,

how they left everything behind in an hour.

(From him, she learned about the uses

for silence, how to look the other way.)

She learned from her best friend how

to be fully integrated into another family.

And still, she’s surrounded by teachers –

the woman in the flat next door who leaves

hand-written recipes and cuttings of flowers,

the man at the corner shop and his houseplants,

the woman on the lunchtime radio warning

listeners of small pensions, the piano teacher

explaining crossing musical lines, particularly

in Bach, how to think of each as a colour,

one shining brightest at any given moment.

She’s learning while sitting in the corner,

a tactic she learned during school lunches,

where she sat alone while the others laughed

their way through the hour. And cooking —

instinctively trying ingredients – was a great

teacher too, and magazines in waiting rooms

and street signs, and of course the prophet Muhammad

المرء يُعرف بأصدقائه almar’ yuerf bi’asdiqayih;

a man is known by the company he keeps).

The seasons were her teachers, and the strict tutor

at school: she never spoke out of turn but was once

made to stand with one foot in the bin,

— another metaphor, she thinks, a lesson of its own —

or how the athletics team were forgiven poor results,

how now she’s a teacher, easy-going and once again,

dwarfed by 16-year-old boys. And the teacher

who said in passing in a hallway that she had talent,

could see what others didn’t in a text, or a problem,

how in that moment her life shifted. How do we stop

long enough to listen, she thinks, and choose

what to hear, to commit to memory, and keep?

iv. WHEN else did you learn?

(What didn’t you learn at school?)

“Outside of school, I learned to boil water for

30 minutes before drinking it, how roses flavour

cakes and remove wrinkles, not to salt rice

as it boils, how to speak to a room of strangers,

read their faces (and when to choose not to read

a face). I didn’t learn how to change a tyre at school,

that a smile is a kind of weapon, how the sun

burns, or that wisdom waits with a newspaper

on a park bench, willing me to slow my walk.

I didn’t learn at school that women make the best

doctors, fighter pilots, policemen, or that all

the answers would soon be held in my palm

(but only for those with electricity, those with WIFI),

or how the weight of information bears no relation

to the act of learning, that learning is

learning to learn, knowing where to look,

discerning the correct question to ask

in order to narrow the playing field.

“How long do you have?” she asks. “I could speak

for a week about what I wasn’t taught in school.”

v. Let’s ask another question –

WHY will we learn in the future?

The woman sits in silence, listens for the voices of those

behind and ahead to appear before speaking.

“What use is knowledge in a vacuum? What benefit

those facts on a screen if we don’t look up to see them

in our ordinary sitting rooms, in the faces of children,

on city blocks, or hanging from the limbs of trees?

For all of human life, earth has rounded our sun

at the same speed. Now men with instruments

and calculations have computers to solve

angles and equations faster than the brain

can comprehend, and yet they tell us

what we sense in our bones: light and then

darkness, the heat of sun and snow glittering

into ice, how a long winter always gives in.

Now, we must seek what we can and can’t see,

prove the black hole in the sky, the body’s failure

to repair (and suggest a cure), calibrate

the speed of time, how it slows both imperceptibly

and perceptibly, together we must measure how

the earth burns; but that learning doesn’t matter

if we can’t access it, and we don’t acknowledge

how we must all hold the answers in our hands.”

vi. And HOW will we learn in the future?

The woman answers without hesitation — “we’ll learn

by having the power to ask questions, making space

for the answers, then listening for the questions

those answers present. We’ll learn by listening.”

This poem includes the ideas and anecdotes of groups of refugee and migrant women at the Maryhill Integration Network (Glasgow) and The Welcoming (Edinburgh). The language appears in italics where the women are quoted directly.

Marjorie Lotfi was born in New Orleans, moved to Tehran as a baby with her American mother and Persian father, and fled Iran with one suitcase and an hour’s notice during the Iranian Revolution. After waiting with family for her father’s return in her mother’s tiny hometown in Ohio, she lived in different parts of the US before moving to New York as a young lawyer in 1996 and then back and forth to the UK, settling in the UK in 1999, and in Scotland in 2005. Marjorie Lotfi’s poems have been published in journals and anthologies in the UK and US (including The Rialto, Gutter, Ambit, Magma, Rattle and Staying Human), included in Best Scottish Poems 2021 and performed on BBC Radio Scotland and BBC Radio 4. Her pamphlet Refuge, poems about her childhood in revolutionary Iran, was published by Tapsalteerie Press in 2018. She was one of the three winners of the inaugural James Berry Poetry Prize in 2021, and her first book-length collection, The Wrong Person to Ask (Bloodaxe Books, 2023) is a Poetry Book Society Special Commendation. In 2024 she won the Forward Prize for Best First Collection.