Carol Richardson is a Professor of Early Modern Art History, History of Art at Edinburgh College of Art, University of Edinburgh. She specialises in institutional patronage, particularly that of the Early Modern period.

She is passionate about the History of Art as the ultimate interdisciplinary subject area, which makes it both inclusive and challenging. She believes it is an antidote to media attention on global crisis and humanity’s inhumanity as art often emerges from, comments on, sometimes resolves and almost always atones for some of our worst actions.

This article is an abridged version of “Weaving the Edinburgh Seven” in The Journal of Scottish Yarns, Issue 5, Spring/Summer 2024

In 2019 Christine Borland, one of Scotland’s leading contemporary artists, was commissioned to make new work in partnership with Dovecot Tapestry Studios.

The result, an intricate and innovative tapestry, honours the first women to matriculate at a university in the Britain, known as the Edinburgh Seven. The colourful three-part artwork is now on public display at the University of Edinburgh’s Futures Institute (EFI) – the former site of Edinburgh’s Old Royal Infirmary, following its exhibition at the V&A Museum in London’s South Kensington.

The group were the first women to study medicine in the UK. Their leader, Sophia Jex-Blake, had been told that, although she was permitted to study, the medical school could not make the necessary arrangements for just one woman, a problem she resolved by recruiting others to join her. Although the women were all listed by the General Medical Council as students for 1869–1870, the city Court of Session ruled that they should not have been admitted in the first place, and, in the end, they were not allowed to graduate. On 18 November 1870, when the women attended an anatomy exam at Surgeons’ Hall, they were met by a large crowd who threw rubbish and mud at them. As a result, male students shocked at their treatment started to act as their informal bodyguards.

They pursued their studies nonetheless and five of the original seven eventually gained their formal qualifications on the continent at Bern and Paris, and their efforts finally led to the UK Medical Act of 1876, which allowed women to practise as doctors.

In 2015, the seven female pioneers were remembered in a plaque at Surgeons’ Hall. In 2019, the University of Edinburgh awarded their medical degrees posthumously, and the seven medical students who accepted the degrees on their behalf are represented in a commission by Laurence Winram, whose commemorative photograph updates Rembrandt’s 1632 painting, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp.

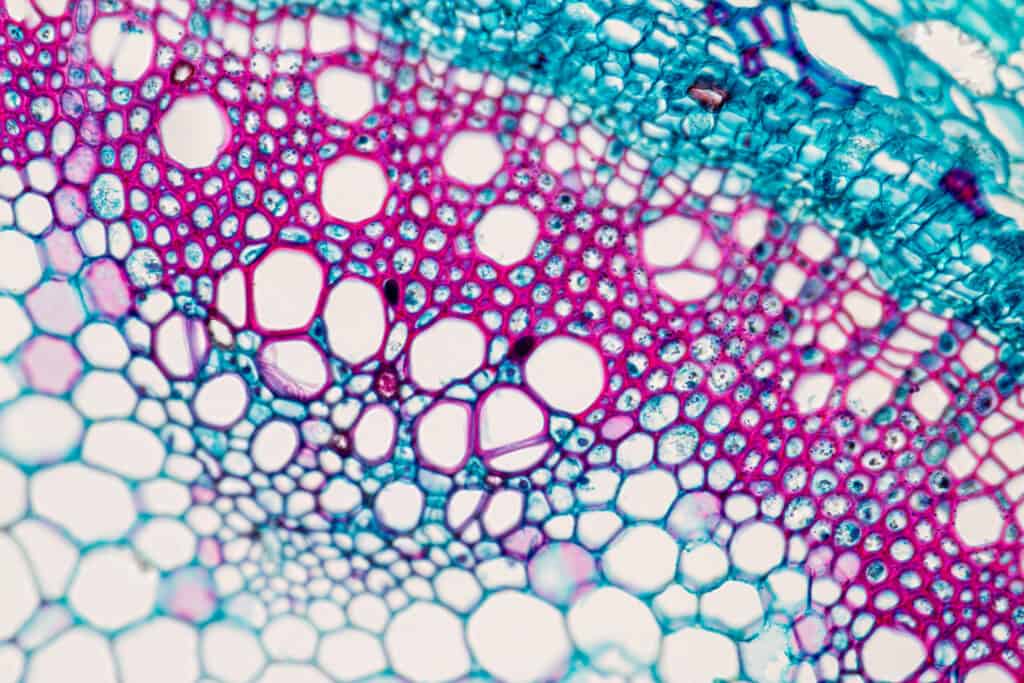

Christine Borland’s designs for the new tapestry commission engage with the medical education encountered by the Edinburgh Seven in the late 19th century, which was not as we might expect today. As well as anatomy, they studied botany at Inverleith House, the home of the Edinburgh Botanic Garden, where they were taught by John Hutton Balfour who was both Dean of the Faculty of Medicine and Regius Professor at the Botanics from 1845 until his death in 1884. Hutton Balfour promoted the use of microscopes which he described as ‘a most important instrument in education’ to examine the cell structures of plants. And it is in microscopy that Borland found inspiration for her work in glass slides of plant specimens that were often stained with textile dyes to clarify their details, choosing a magenta and cyan colour scheme for the tapestry to represent the dyes used in both the scientific staining of cells and textile in the 19th century.

Cells and CGI

Taking a story back into history, and even prehistory, then projecting forward to consider its contemporary relevance, is a common theme in Borland’s creations. As a result, ancient materials and crafts are as familiar in her work as computer coding and 3D printing. The Edinburgh Seven tapestry project pushed this way of working in new and unexpected directions, not least because it took place during the Covid-19 pandemic which severely limited access to research resources and in-person collaboration.

An important inspiration for the finished tapestry was cloth, and its practical, material and even symbolic properties. Through weaving, Borland connects some of the most ancient associations between women, wisdom, and the very creation of life itself. In Norse mythology, the Norns are the spinners of fate, sitting at the base of the great tree that represents the world, Yggdrasil. In Ancient Greece, Arachne was a proud weaver who challenged Athena, goddess of wisdom as well as weaving, and was turned into a spider for her hubris. Zhi Nu is the ancient Chinese goddess of weaving (and knitting), identified with the star Vega, one of the brightest in the sky. These are weaver goddesses weaving the heaven’s celestial canopies which wrap the world itself.

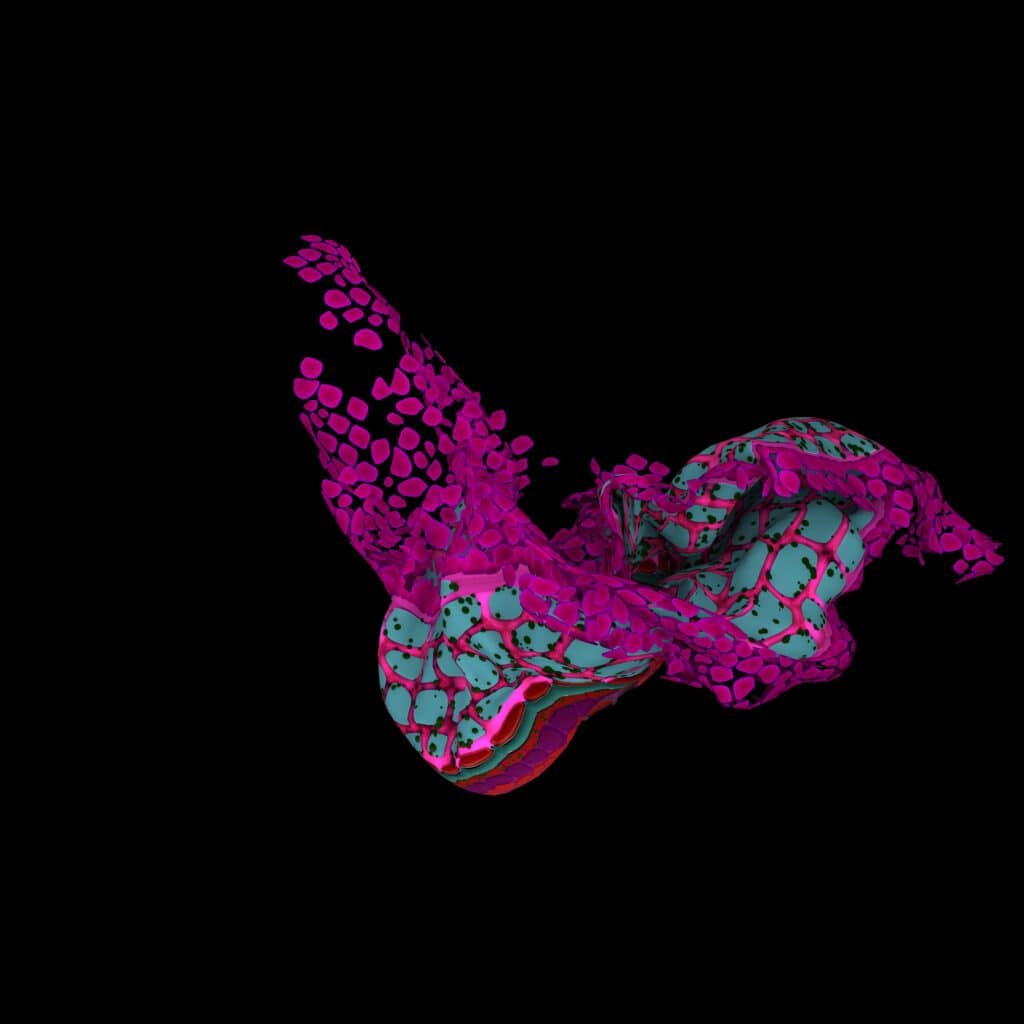

Motion capture, usually more closely associated with big budget cinema and video games, was originally designed to support medical research on movement and gait analysis, and Borland wanted to return to those medical origins and incorporate this process into her design for the tapestries. Dressed in a tight-fitting suit marked with sensors that enabled computer analysis, she tracked her movements with sweeping cloths to uncover their hidden or overlooked uses, such as holding, folding, cleaning, wrapping, hanging, and playing with cloth to isolate its movements.

But while motion-capture tracked the movements of the body, the cloth itself was absent and had to be reinserted digitally. The films were paused to find frames that represented stilled moments in choreography. Passing through the digital wireframe model, the structures were then mounted with the patterning and colours Borland derived from the botanical cell-structure drawings and slides, building them up slowly and carefully in layers. The end results fashioned dancing cloths that are animated, independent of, and yet dependent on, the body.

Weaving process

The designs were then produced as two-dimensional digital prints that were then passed to the Dovecot tapestry team, led by Master Weaver Naomi Robertson, who in turn had to develop complex processes to interpret them. Through shading and pattern, the tapestries on the loom took on a vivid, three-dimensional quality that reflected Borland’s processes. Originally intended to be displayed flat, it was subsequently decided that the tapestries would be sculpted and manipulated into the 3D forms their finished shapes now embody. This reflects the circularity of Borland’s process, embedded in the tapestries and their public unveiling, first of all at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, from March to May 2024, before returning to Edinburgh and the old Royal Infirmary building, now the University of Edinburgh Futures Institute.