Reacting to crises is costly: in human, social, and financial terms. From rising health inequalities to escalating climate pressures, the price of inaction before harm hits is mounting.

Yet despite decades of policy ambition, our public systems – from healthcare to environmental management – remain locked into repairing harm after it occurs.

What would be better than this?

An economy that prevents harm in the first place offers a different path: one that shifts resources, relationships, and imagination upstream to where the roots of challenges lie. Such an economy is designed to reduce inequality, strengthen communities, and create the conditions for wellbeing (incidentally, the ‘conditions of wellbeing’ speaks to the original meaning of the word ‘wealth’…)

There are two hitherto untapped forces that will help with the task of building such an economy: collaboration is essential for the hard task of upstream change, and compassion keeps people connected to why such work matters.

From Crisis to Prevention: The Urgent Shift Upstream

Treating symptoms or not pointing a wide enough lens on where change needs to happen will almost inevitably result in ‘fixes that fail’: dealing with the same problem again and again, because the root of the problem has not been identified, let alone solved.

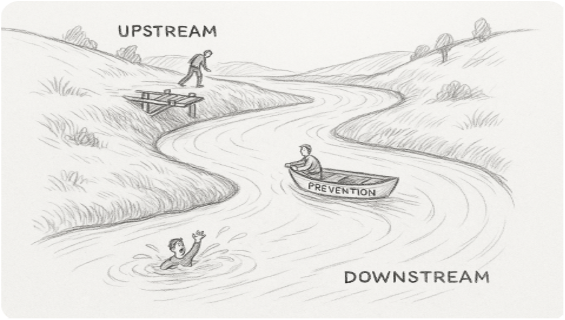

The metaphor of a river is often used to explain the difference between downstream actions that come into play after the damage has been done, acting on the symptoms and helping handle the harm, on the one hand; and, on the other hand, actions upstream that prevent harm from happening. Upstream prevention is about making change long before symptoms emerge.

AI-generated image.

A focus on upstream prevention shifts the attention from simply reacting to individual crises (critical though that is in the short term) towards reshaping the systems that produce them in the first place.

This offers the potential to reduce the fiscal costs governments bear in responding to harm, by avoiding the need for repeated downstream interventions. But the benefit beyond that is building the conditions for fairer participation, improved life chances, and thriving communities.

Crucially, given the extent of economic inequalities and the very real constraints these impose on people, upstream prevention needs to encompass identifying and addressing the structural and systemic conditions that create harm. This requires focusing on the economic drivers of inequality: such as insecure work, poor housing, low wages, lack of access to quality education, and unequal distribution of resources-that undermine people’s choices and erode wellbeing.

The impact of efforts to prevent harm will be limited unless they extend upstream to reshape the economy.

Working Upstream: Prevention and Economic Transformation

The challenge is that, for a range of reasons, addressing constraints people face by working on their economic roots is a heavier lift than papering over the cracks with sticking plasters.

Economic system change is hard.

For instance, the current economic configuration derives staying power due to the very nature of its incumbency, held in place by routine ways of doing things, existing legislation and policies, and path dependencies. As Bache explains, bureaucracies come with an ‘inbuilt inertia…that give a comparative advantage to existing ideas and practices’. One aspect of this is informal and cultural: current systems are held up by established networks, relationships and hierarchies of status. Consequently, there is a powerful weighting against upstream change, no matter how necessary.

Public services are making real efforts to shift towards prevention, yet the work remains extremely complicated. Internal processes – whether in public services, the finance industry, or other sectors – often make it difficult to go against established ways of working, let alone to prioritise upstream change. Unless institutional and governance arrangements evolve to actively support and reward the economic shifts required, progress will be limited, and much energy will continue to go into managing the consequences downstream rather than addressing their causes.

There is also a political bias and power imbalance to contend with. Reshaping the prevailing economy can be hindered by recalcitrance from those who feel the current system is adequate or inevitable. Working to change the system will confront those who believe the current economic model benefits them and who worry that shifting to an economy designed for greater fairness and sustainability might bring a loss of status, power or influence that they enjoy by virtue of the current economic set up. These actors tend to use their considerable influence to reinforce and uphold dominant thinking, thus perpetuating tinkering around the edges of the current set-up and responding to its symptoms, downstream, one at a time.

Clearly the shift towards prevention is not ‘just’ a technical process, or a single policy: the task is much broader. It depends on how we think, how we lead, how we know, and how boldly we can imagine change.

So, how can these choppy and challenging waters of upstream change be chartered?

Collaboration: key to upstream change

The work of creating an economy that prevents harm cannot be done by any one organisation or sector alone. Collaboration is vital, and collaboration that is deeper than coordination and more courageous than compromise. This is collaboration as collective leadership – a way of working where responsibility is shared, where relationships are privileged, and outcomes are co-created.

Collaboration for upstream change needs to be guided by paying attention to 4 key principles. Firstly, seeing the whole system: recognising that housing, health, education, justice, employment and the environment are inseparable. It also calls for inquiry: a willingness to be curious, to learn together, and to adapt as challenges evolve. It further depends on relational trust: people who know one another well enough to face tension without breaking apart. And finally it thrives on emergence: the openness to experiment, disrupt habits, and allow new solutions to take shape.

When collaboration is rooted in these principles, it offers an effective approach to making upstream economic change possible. Without it, efforts remain fragmented and short-term. With it, we build the collective capacity to shift resources and energy toward preventing harm rather than repairing after the damage has been done.

Compassion as reason to go upstream together

Collaboration is the method – done well it shows us the way forward. But compassion gives the reason to act – fuelling efforts to confront inequality, shift power dynamics, and create lasting systemic transformation.

Compassion here is not about optional kindness, but humanity, understanding and action. It helps people and organisations who are working together to resist the pull back downstream to familiar crisis responses. It ensures that economic reform is not only effective but humane: centred on the lives it seeks to improve.

Conclusion: no time to delay

The case for an upstream economy is clear: it is more sustainable, more equitable, and ultimately more cost-effective than the largely reactive systems of today. Yet prevention this far upstream is also profoundly difficult to achieve. It asks us to challenge short-term thinking, rigid budgets, and performance regimes that reward firefighting over foresight.

So there is no time for delay. The costs of crisis – social, environmental and financial — are escalating every year. Each moment upstream change is avoided, the harder it becomes to shift course.

The path forward is demanding but possible. This is not the work of individual heroes, but of collaboration across society — public servants, businesses, communities and citizens learning to lead together. By grounding our efforts in collaboration that sees the whole system, and by carrying compassion as the motivation that sustains upstream work, we can begin to build an economy that enables people and planet to thrive.

The choice is stark: continue bearing the rising costs of crisis, or committing to the difficult but transformative work of prevention. The work is hard, the time is now — and the future depends on it.